BACKGROUND

Zhangqiao Community is located in Jiaxing Road, Hongkou District, Shanghai. The Shajinggang River runs from north to south through the area, which is bounded by Dongshahonggang Road, Shahong Road, and Jingdong Road, with Zhangqiao Road cutting across the middle. Nearby are Youdian Xincun Station on Metro Line 10 and Linping Road Station on Line 4, and the area is close to major arteries such as Siping Road, Dalian Road, and Zhoujiazui Road, offering convenient transportation. Most surrounding slums have already been demolished and redeveloped into public facilities such as Heping Park, the First Affiliated High School of East China Normal University, community activity centers, as well as high-end residential developments like Ruihong New Town.

Historically, the area where Zhangqiao Community is located formed in the early Ming Dynasty. With the development of trade, the area gradually became populated and evolved into a market town. By the early Qing Dynasty, it had become a key gathering place for rural residents to trade. Later, with the formation and development of Hongkou Port and Gongping Wharf and the opening of Shanghai as a treaty port, the decline of inland waterways affected the area’s prosperity.

Around the 1860s, influenced by foreign capital inflows, industrialization, and conflicts such as the Taiping Rebellion, large numbers of impoverished farmers migrated to Shanghai in search of work. Unable to afford rent, many settled on wasteland and riverbanks. With the establishment of factories and railways, workers from Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and surrounding regions clustered in this area. During the second Sino-Japanese War, a large influx of refugees moved to the north bank of Suzhou Creek, and housing was heavily damaged. Between 1945 and 1950, many landless farmers from Jiangsu and other regions migrated here and settled in wartime trenches and vacant land.

As the population grew, large amounts of domestic waste accumulated around abandoned military facilities. During the Great Leap Forward in 1958, campaigns were launched to clean waste, fill waterways, and build roads, and Shahonggang was filled in to become a roadway. Subsequently, population growth combined with economic stagnation placed increasing pressure on the environment. From the late 1960s onward, residents began to appropriate space spontaneously, and residential forms gradually evolved. In the 1970s, the municipal government introduced improvement measures such as piped water connections, individual electricity meters, and centralized waste removal.

In 1992, Shanghai initiated large-scale urban renovation of old neighborhoods. Over the following years, a sizeable residential area gradually formed around Zhangqiao Community, followed by a prolonged period of stalled municipal development. In the late 1990s, with economic reform and real estate development, Shui On Group planned and constructed Ruihong New Town, leaving Zhangqiao Community as the last remaining slum.

| Period | Building Features | Building Materials | Infrastructure | Resident Origins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – 1945 | “Boat dwellings,” “ground-hugging shelters” | Bamboo, branches, straw, mud, tar felt, etc. | Extremely poor living conditions; no electricity or water supply | Refugees from northern Jiangsu and factory workers from Jiangsu – Zhejiang regions |

| 1950s – 1960s | Predominantly single-story houses | Bricks, wood, cement | Infrastructure gradually improved | Same as above |

| 1970s – 1980s | Illegal extensions; horizontal and vertical expansion | Diverse and ad hoc, depending on household conditions | Rapid population growth with insufficient governmental support; increasing scarcity | Large numbers of migrant workers attracted by low rents |

| 1990s – | Extensions gradually ceased | — | — | — |

ETHNOGRAPHY

- Resident-driven construction and spatial characteristics

Modes of spatial expansion: Due to high density and land scarcity, residents commonly expanded their homes by “building upward” and “encroaching outward.” Vertical expansion involved adding floors to existing one-story buildings, while horizontal expansion encroached into public alleys, resulting in extremely narrow passages.

Structural characteristics: Constrained by small plots, interior staircases are often steep. Most houses share walls with neighboring units, and dwellings with multiple independent façades are rare.

Negotiated constructions among neighbors: In the absence of unified planning and regulation, neighbors negotiated informally to meet daily needs, resulting in unique connective structures such as shared balconies, inter-house passageways, and adaptive reuse or partial occupation of abandoned neighboring houses.

- Low-tech and temporary material use strategies

Limited economic resources led residents to widely reuse inexpensive, readily available materials for construction and repair. Examples include replacing windows and curtains with advertising banners, using plastic sheets as canopies, assembling rags, scrap wood, metal pipes, and birdcages as exterior walls, and even repurposing bottled-water containers as drainage pipes.

- Derived living environment and social issues

Severe lack of infrastructure and public services: Illegal construction, weak cross-district governance, and long-term pending demolition reduced incentives for both government and residents to invest. Consequences included dilapidated buildings, unmanaged waste accumulation, and inadequate sanitation (reliance on public toilets outside the area or chamber pots).

Security and social relations: Historically and currently, the area has faced safety concerns. Residents commonly installed multiple locks, papered windows to prevent peeping, embedded glass shards on walls, or sealed windows as defensive measures; theft occurred frequently. Many migrant tenants were wary of each other and avoided outside contact, while relationships among long-term residents became increasingly distant due to everyday conflicts.

Residential safety and environmental quality concerns: High-density illegal extensions severely blocked light and ventilation. Combined with window-sealing practices, interiors often required artificial lighting even during the day. Aging materials and nonstandard construction posed risks such as leaks, exposed wiring, overly steep staircases, and potential structural collapse, threatening residents’ daily safety.

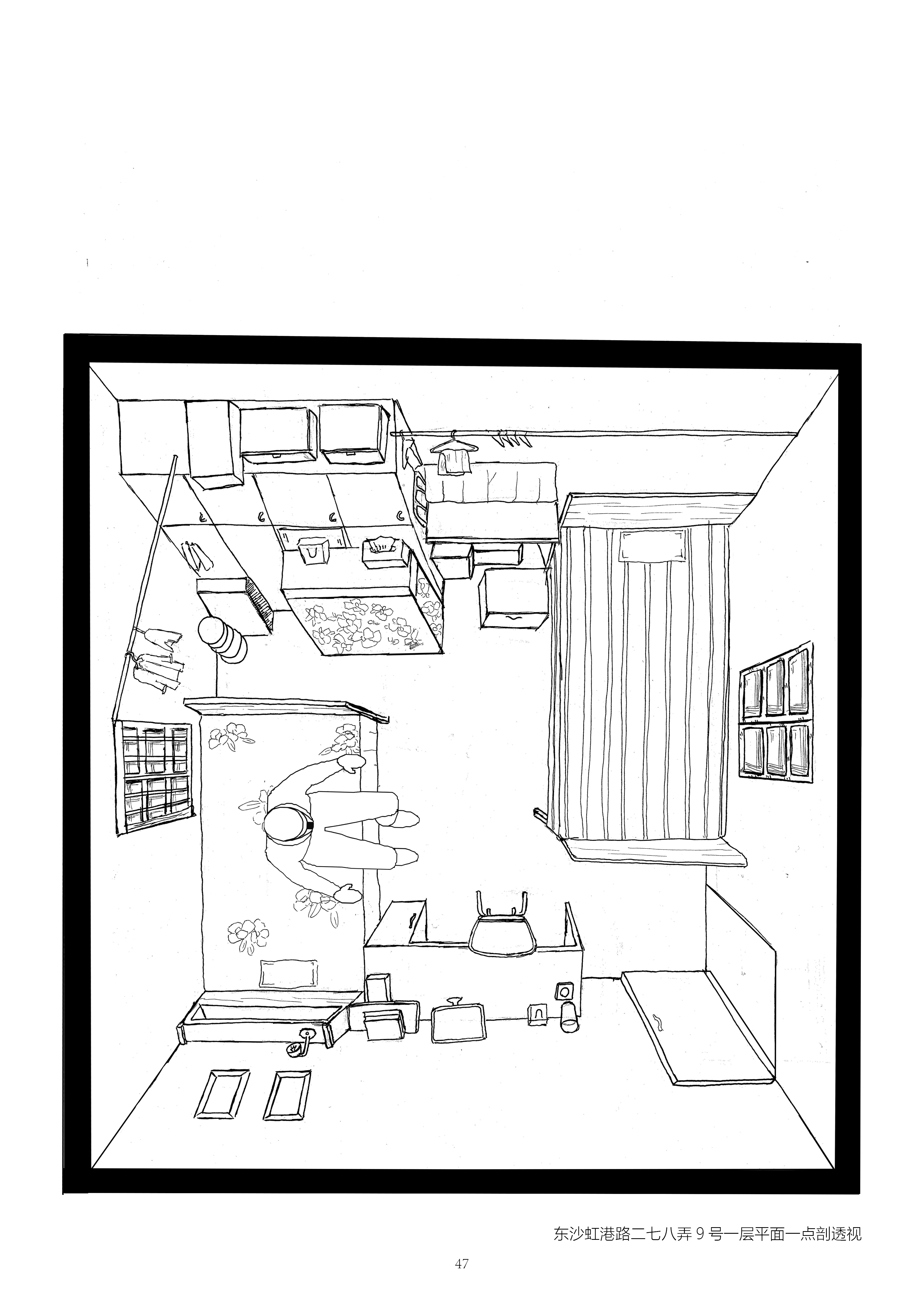

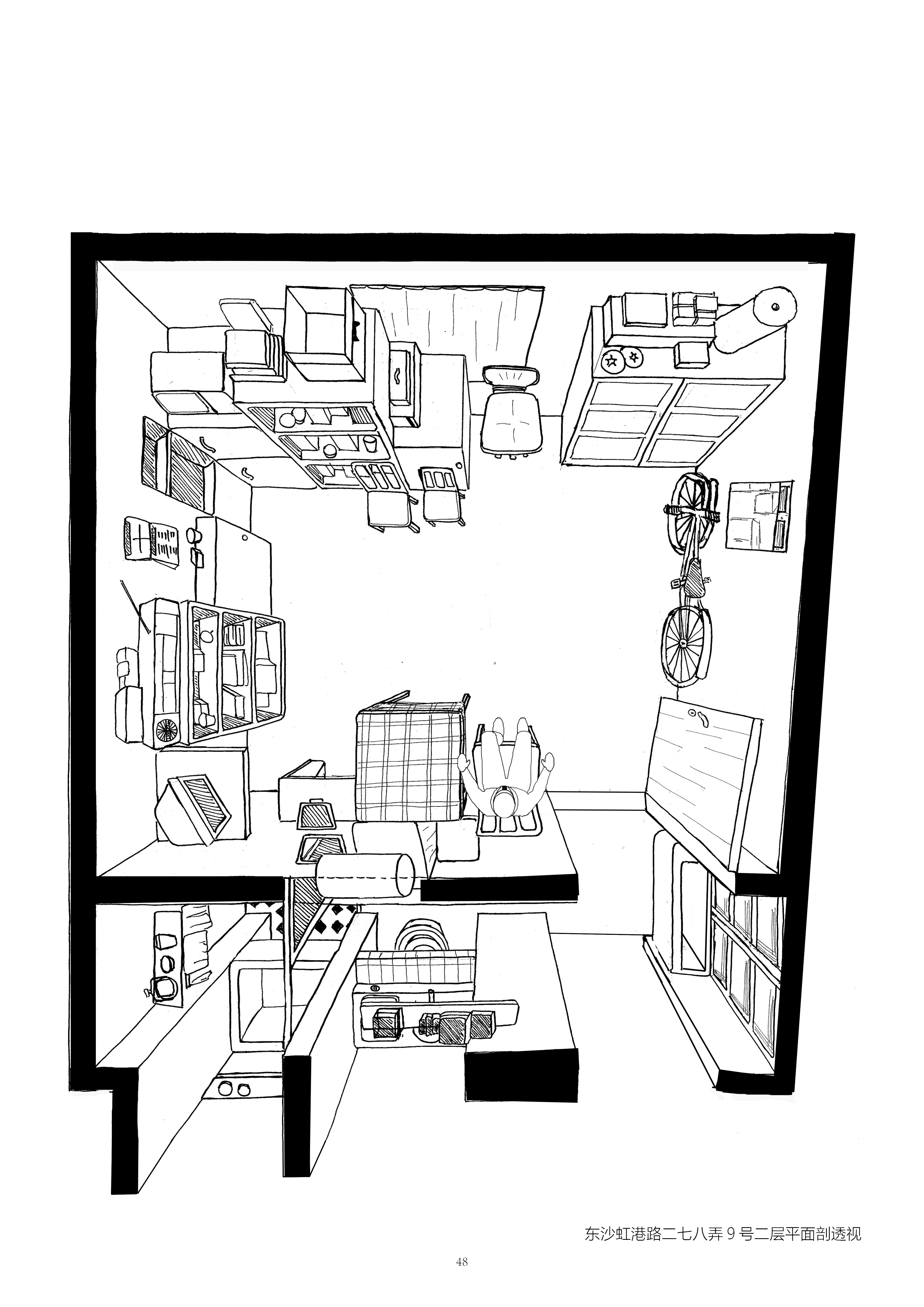

This field work documented the built environments of two households - No. 9, Street 278, Dongshahonggang Road and No. 16, Street 302, Dongshahonggang Road. I present the first household as an example:

Address: No. 9, Street 278, Dongshahonggang Road

Floor area: Approximately 60 m² (three stories)

Per capita living area: Approximately 20 m²

Household background: Originating from northern Jiangsu

Housing condition and evolution: The three-story house contains a living room, kitchen, and bathroom on the first floor; bedrooms on the second floor; and storage on the third floor. Originally occupied by Ms. Zhu’s parents, the couple moved in after marriage due to limited space in Mr. Sun’s family home. Ms. Zhu’s mother later moved to live with her son. In recent years, the house has been rebuilt to accommodate a growing family and improve living conditions.

COMMUNITY WORKSHOP

Following this project, we organized co-design workshops to present design proposals for public space renovation, gathered feedback, and invited residents to co-design with us.